Birmingham research could improve care of patients living with artificial heart pump

New research funded by the British Heart Foundation (BHF) aims to inform and improve clinical care for those living with an artificial heart pump.

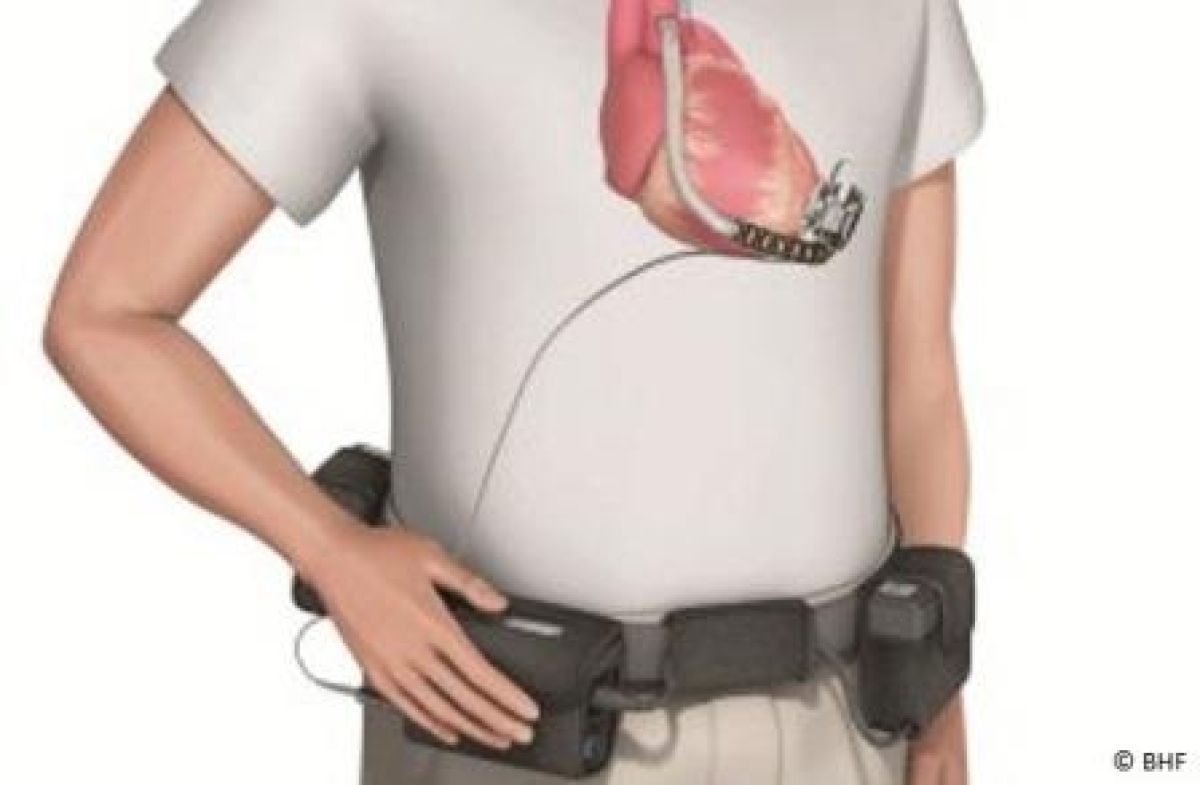

A left ventricular assist device (LVAD) is a battery-operated, mechanical pump surgically implanted into patients who have end-stage heart failure. It is sometimes given to people who are on the waiting list for a heart transplant, and it helps the failing heart by restoring normal blood flow.

There are around 300 people currently living with an LVAD in the UK. While the device is both life-saving and symptom-relieving, recipients must undergo open heart surgery, and then have to carry the portable LVAD equipment with them at all times. These factors, as well as the need to sleep attached to a monitor, can have a detrimental impact on patients’ quality of life.

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) – often in the form of short questionnaires – can help clinicians to assess quality of life through identifying what is going well and what might need addressing in a patient’s care.

However, people living with an LVAD believe that current PROMs are not fit for purpose, and that those used to measure quality of life do not address the wide range of problems that living with an LVAD presents. This includes psychological issues, such as anxieties over the equipment and impact on body image.

Now, thanks to £240,000 funding from the BHF, Birmingham Health Partners researchers will work with 150 LVAD patients from across the UK to produce a new PROM that will better measure their quality of life.

The research will be led by Dr Anita Slade, of the Centre for Patient Reported Outcomes Research (CPROR) at the University of Birmingham, who is based within the ITM. The CPROR is supported by the NIHR Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre – also within the ITM.

“Although an LVAD can extend the life of those living with severe heart failure and improve their symptoms, it does bring its own issues and requires substantial environmental and lifestyle changes for recipients and their families.

“Through discussions with a small group of people who have experience of life with an LVAD we have found that current patient related outcome measures (PROMs) do not address their specific needs and therefore are not able to accurately monitor changes in their quality of life. Understanding this is crucial when developing and evaluating new interventions to improve their health and well-being.

“Developing a new PROM with input from patients will ensure their voices are central to their care, and allow us to better understand how to improve their quality of life now and in the future.”

– Dr Anita Slade

It is hoped this research will inform and improve the clinical care of those living with an LVAD and even advise future research, policies and design proposals for the device.

Dr Lucie Duluc, Research Advisor at the BHF, added: “Implanting an LVAD can be life- saving and also buys more time for those awaiting a heart transplant. Some patients who were too unwell to walk around can see massive improvements to their life once receiving an LVAD, with many able to return to normal activities.

“However, recipients have to adapt to the many changes this makes to their life, and this can have an adverse impact on their health. Patients say that current PROMs do not address this, so this research will be pivotal to better reflect the real experience of people living with an LVAD. By putting patients at the core of this research, this could ultimately help shape the care they receive.

“We can only fund research like this thanks to the generous support of the public, in driving forward our mission to beat heartbreak forever.”

James’ story

James Maund, aged 48 and from Gloucester has been living with an LVAD since 2016 and will participate in this project.

The father-of-four said: “I was diagnosed with dilated cardiomyopathy and was told that my heart had enlarged and was functioning at 16%. Doctors told me I would need a heart transplant, but would need an LVAD first to get well enough to be eligible.

“After a high-risk operation, I began living my life with an LVAD. For the first three months, there was a lot of concern, including how I was going to support my family. Psychologically, I struggled with how this would affect my body image.

“I have come to terms with living with an LVAD, as without it, I wouldn’t be alive. I’m pleased that the views of people like me will be reflected in the development of the PROM.”